Fairing Recovery Compendium

This article will be regularly updated based on the latest information (list of recent changes can be found at the end of the article). You can easily access the article from the main menu in the “Compendiums” section.

Last Update: December 23, 2020

(changelog)

Satellites being encapsulated inside the Falcon 9’s fairing prior to the Iridium-4 launch (Credit: Iridium)

Fairing is a two-piece protective shell made of aluminum and carbon composite at the tip of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. Its purpose is to protect the payload (usually a satellite) from acoustic and atmospheric effects during launch. It’s not obvious from photos but the fairing is actually almost 14 meters tall. Due to the materials used and its size, production of a fairing is time-consuming and costly (SpaceX produces the fairings in-house and the total cost is 5 or 6 million USD). So it is no wonder that the company would like to recover the fairings in order to use them repeatedly, just as it does in the case of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy boosters. This article summarizes all the important information about SpaceX’s fairing recovery project and is being updated regularly.

Skip to section:

- Fairing recovery process

- Project history

- Fairing upgrades

- First serious recovery attempts

- First successful recovery and reuse

- Ms. Tree in general

- Ms. Tree in SpaceX fleet

- Costs

- List of recovery attempts

Note: This article was originally written in Czech for ElonX.cz

Fairing recovery process

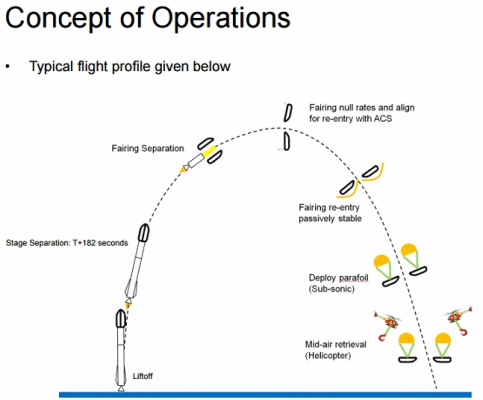

In the beginning, SpaceX probably considered various methods of recovering the fairings. For example, one of the concepts included catching the fairings mid-air using helicopters. However, this idea was eventually abandoned.

Leaked slide showing the original plan to recover fairings using helicopters

The method eventually chosen by SpaceX is similar, except in the final phase the fairing lands in a net aboard a fast ship. Each fairing is equipped with avionics, nitrogen thrusters and a steerable parachute. What does such a recovery process look like explained Elon Musk in an interview:

The actual complexity of recovering the fairing is so nuts. Like, I’m not sure we should’ve done it. We have done it. But each fairing half is like a tiny spacecraft with little thrusters on it. So when it’s coming in from space it’s in vacuum. And little thrusters controlling the fairing ’cause it’s gotta come down round side-down ’cause that’s where it’s got a heat shield. It’s got a thermal protection or heat shield on the outer surface but not on the inner surface. So it’s gotta come down with the rounded surface coming down. And it’s gotta maintain its attitude as it comes in through space. And it comes in hot. If you look at the fairing entry video you see super-heated plasma and sparks and stuff flying off of it. It’s coming in at basically five times faster than a bullet from an assault rifle. It’s insane.

And then it hits the atmosphere, it goes subsonic. We deploy the parachutes. And the parachute itself is a steerable parachute with actuators (note: possibly Sherpa from MMIST). So it’s steering itself down and coming down on glide path. And then the boat closes a data link with each fairing half. And the boat adjusts course automatically. And then the two just maneuver to touch each other. And we only just solved that in the last launch.

To help you visualize all this better, here is an animation of the whole process made by Reddit user KerbalEssences:

Project history

It is not clear when exactly SpaceX started working on the fairing recovery project, but the public first learned about these efforts in June 2015 when Elon Musk stated that a washed up fairing found in the Bahamas would be helpful for fairing reusability. However, first evidence of SpaceX actually working on this came in March 2016. In amateur footage from the SES-9 launch, it could be seen that the fairing used maneuvering thrusters (see video below at 5:20 and 5:27 timestamps). In June 2016, Elon Musk said that “autosteering chutes” would be added to the fairings soon.

The next significant acknowledgement of fairing recovery came in February 2017 at a press conference for SpaceX’s first launch from pad 39A. SpaceX’s President Gwynne Shotwell confirmed that the company really is trying to recover fairings, and estimated that some meaningful results could be achieved during 2017.

The first serious attempt to land a fairing using a parafoil took place during the SES-10 mission in March 2017. Elon Musk said at the post-launch press conference that the fairing had landed in one piece and indicated that in the future, the fairings would be landing on some kind of “bouncy house” to prevent contact with corrosive sea water.

SES-10’s success apparently filled Musk with optimism because a few days later he said on Twitter that a fairing would be reused during 2017. He also posted a cool video showing the SES-10 fairing floating in space before reentry:

In 2017, several additional fairing splashdowns were conducted and the project seemed to be going well. However, in June 2017, Elon Musk stated on Twitter that the company encountered problems with the self-steering parachutes. At the same time, he estimated that the issues would be resolved by the end of the year.

Fairing upgrades

Part of the solution was to develop an improved version of the fairing that SpaceX tested in the fall of 2017 in Ohio where the world’s largest thermal vacuum chamber is located. This upgraded fairing dubbed “Fairing 2.0” was first used on the Paz mission in February 2018. According to Elon Musk, it is slightly larger in diameter and is better optimised for recovery.

Additionally, at the end of 2018, SpaceX started adding thermal protection to the tip of the fairing (first used on the GPSIII-SV01 mission) which could be seen in detail during the Amos-17 and STP-2 missions in 2019:

First serious recovery attempts

Not only did SpaceX test out a new type of fairing on the Paz mission, a special ship was deployed for the first time as well. The concept of landing the fairings on a bouncy house was apparently abandoned and SpaceX instead equipped a very fast ship named Ms. Tree (previously named Mr. Steven) with a metal structure and a large net that could catch the descending fairings. During the Paz mission, the fairing missed the ship by a few hundred meters and landed in the water. Subsequently, Musk explained on Twitter that with a slightly larger parachute, landing in the net should be possible, as the fairing would descend more slowly. It’s unclear if a larger parachute was eventually implemented, or if it’s even planned. SpaceX made several more attempts to catch fairings in the net during 2018, but none were successful.

In March 2018, Elon Musk announced that SpaceX was preparing to conduct helicopter drop tests to practice fairing recovery with Ms. Tree. These trials were supposed to take place “in a few weeks,” but didn’t actually start until the fall of 2018. Several test runs took place and they generally worked like this: The entire thing took about half an hour, starting from when a Blackhawk helicopter picked up a fairing from a barge. The helicopter then ascended to an altitude of 3.5 km and dropped the fairing. The fairing then opened a steerable parafoil and Ms. Tree tried to catch it in its net.

Ms. Tree didn’t succeed in catching the fairings during these tests. However, judging by the released videos, some of the attempts were very close:

By the way, the fairing consists of two halves, but SpaceX initially practiced landing with only one half (the other one didn’t have a parachute). But SpaceX’s goal is to recover both halves during every launch and therefore, starting with Fairing 2.0, both halves have been equipped with parachutes. At first, it wasn’t clear how SpaceX intended to go about catching both fairing halves but in August 2019, Elon Musk confirmed that the company would use a second ship.

However, during the SSO-A mission in December 2018, both fairing halves landed softly in the water very close to the ship and were pulled out quickly. Elon Musk said afterwards that it might be possible to reuse these fairings after drying them out. During the Arabsat 6A mission in April 2019, both fairing halves were recovered after landing in water (Ms. Tree wasn’t equipped with a net at the time) and Elon Musk announced afterwards that the fairings are undamaged a will be reused on a Starlink mission in 2019. He also confirmed it would be the first time they’d be reusing fairings. That probably means that the similarly recovered fairings from SSO-A won’t be reused after all.

During the Starlink v0.9 mission in May 2019, both fairing halves were also recovered from the water by SpaceX ships. Photos shared by Elon Musk showed that SpaceX didn’t equip the fairings with acoustic tiles. This might explain why the company plans on reusing fairings on their Starlink launches – if the main problem with fairings landing in the water is the sea water contamination of the tiles, they can just remove them afterwards and still reuse them for Starlink missions.

First successful recoveries and reuse

The first successful recovery of a fairing finally took place in June 2019 during the STP-2 Falcon Heavy mission. It was the first recovery attempt on the East Coast for the newly renamed ship Ms. Tree and even though the attempt was made in the dark, the ship still managed to position itself correctly under the descending fairing half for it to land in the net. For SpaceX, it was the first fairing recovered in this way and since it did not come into contact with water, it should be easy to reuse it on a future launch.

The next recovery attempt took place in August 2019 during the Amos-17 mission. SpaceX again managed to land the fairing in the net and Elon Musk shared a video of the landing:

These initial successes led SpaceX to renting another ship that would be used to catch the other fairing half during each launch. The ship’s name is Ms. Chief (formerly Capt. Elliott) which is mostly identical to Ms. Tree and they were built together in 2014 by the same company. Ms. Chief has been stationed in Port Canaveral since August 2019 and in October it was equipped with metal arms and a net used to catch fairings.

Ms. Chief attempted to catch a fairing for the first time in December 2019 during the JCSAT-18/Kacific-1 mission but was unsuccessful. Several more attempts followed but the first successful fairing recovery by Ms. Chief happened in July 2020 during the ANASIS-II launch. That was also the first mission during which both fairing halves managed to land in the nets:

In November 2019, SpaceX confirmed that the two fairing halves from the Arabsat 6A mission would be reflown on the upcoming Starlink v1-1 launch, just as Elon Musk suggested in April 2019. The mission was successful, but rough seas prevented SpaceX from recovering the fairings again.

The first successful recovery of a full set of reused fairings happened during the Starlink v1-6 in April 2020. Fairings from the Amos-17 launch were used and then recovered again after landing in the ocean. This was also the first launch of a reused fairing that previously landed in a net. All previously reused fairings had to be recovered from the ocean.

The first time a fairing half flew for the third time was during Starlink v1-12 in October 2020.

The SXM-7 mission in December 2020 was important because it was the first time a reused fairing flew on a non-Starlink mission.

In August 2020, a sixth fairing half successfully landed in a net during the Starlink v1-10 mission. SpaceX then shared a great video of the landing:

Ms. Tree in general

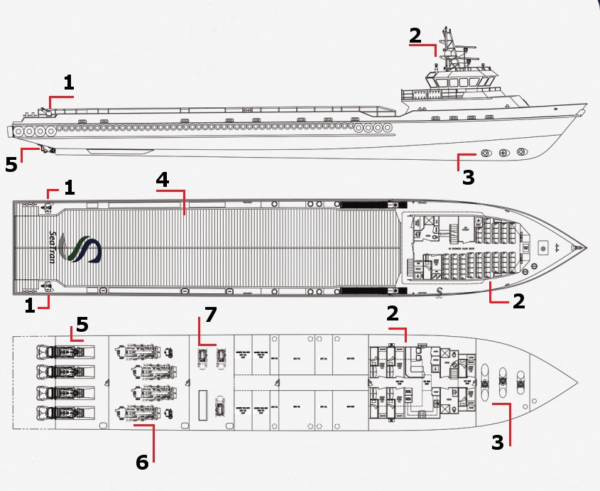

Note: The following information mostly applies to Ms. Chief as well since it’s an almost identical ship.

Ms. Tree is a modern civilian vessel that was manufactured in 2014 by Gulf Craft for SeaTran Marine. The ship was originally named Mr. Steven after SeaTran Marine’s CEO’s father and was primarily used to transport ship crews and material to other vessels or oil platforms. However, SeaTran Marine filed for bankruptcy in 2019 and the ship was purchased by Guice Offshore, a company which previously only operated the vessel for SpaceX. The new owner then renamed to ship to GO Ms. Tree.

Ms. Tree is 61 meters long and 10 meters wide. It is powered by four Caterpillar 3516C-HD diesel engines, each with a power output of 1920 kW at a maximum of 1600 rpm. Total power is 10,300 horsepower. The ship does not have a classic propeller or rudder and uses modern water jet propulsion, basically making it “a rocket on water”. The ship contains a total of four water jets from the Hamilton company.

These jets are becoming increasingly common because they have many advantages over conventional propulsion. Here are some key benefits:

- Almost zero rotation speed, so it’s possible to turn 360 degrees on the spot

- Precise control at all speeds

- Perfect maneuverability while holding the vessel in place

- More efficient at higher speeds than conventional propulsion systems

- The vessel can be stopped from full speed in a relatively short time

Legend:

- Water cannon

- Bridge and crew compartments

- Thrustmaster thruster

- Work area

- Water jets (Hamilton Jet HT810)

- Main engines (Caterpillar 3516C-HD)

- Generators (Caterpillar C93)

Ms. Tree’s hull is made of high quality aluminum alloy. This lowers the ship’s weight (dry weight is about 400 metric tons). The aluminum alloy also has high corrosion resistance. The combination of all these factors allows the vessel to achieve high speeds. Under favorable conditions, Ms. Tree is able to reach 32 knots (60 km/h) and it also has excellent maneuverability. These are the main reasons why SpaceX chose this type of vessel.

Ms. Tree in SpaceX fleet

SpaceX began leasing Ms. Tree at the end of 2017. The vessel initially spent a short period of time in Port Canaveral, but at the beginning of 2018, it started operating on the West Coast, in Port of Los Angeles, California. The reason for this may be that many Falcon 9 launches were planned from California in 2018, and also the port is very close to the SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, so it was easier to make modifications quickly to the ship during the initial fairing recovery program.

Ms. Tree has undergone many modifications while being part of SpaceX’s marine fleet. It all began with the installation of four steel arms and a net. This small net was then replaced by a stronger net of the same size. Eventually though, the whole thing was dismantled and replaced with longer arms and a much larger net. This work was finished on 12 July 2018, and the new net is estimated to have an area of up to 3,600 square meters, which is more than four times the area of the first net. By way of comparison, the autonomous droneship used for Falcon landings is only about 10% larger with dimensions of 91 x 52 meters. In addition to reducing the required landing accuracy, another advantage of the larger net is that the net completely covered the crew section. Therefore, there was no need for an additional barrier to protect the crew on board the ship during landing attempts.

The ship was also later equipped with an additional smaller net which is used to pull fairings out of the water:

At the end of 2018, Florida Today reported that Ms. Tree would soon be returning to Port Canaveral, Florida, in order to support the East Coast launches. There are only a few California launches planned in 2019 and 2020, so it’s expected that Ms. Tree will stay on the East Coast at least until SpaceX proves that the method of catching fairings in a net is feasible. The company can then lease a second ship and decide whether Ms. Tree stays in Florida or returns to the West Coast.

Mr. Steven’s first opportunity to catch a fairing after moving to the East Coast in January 2019, was supposed to be during the Nusantara Satu mission on February 22, 2019. The ship left port two days before the launch and headed toward the landing area hundreds of miles off the coast. However, right before reaching the landing area, the ship unexpectedly headed back to port. When the ship returned to Port Canaveral, it was visibly damaged – two of the four metal arms were missing and the net was gone. Afterwards, the remaining arms were removed by technicians. We still don’t know exactly what happened at sea and what the scope of the damage was, but in addition to the broken arms, one of the radar antennas and the boarding bridge have also been damaged. Ms. Tree finally received new metal arms and a new blue net in late May 2019.

Costs

The success rate of this method of fairing recovery may always be relatively low, partially due to unpredictability of wind conditions at sea. So is the whole thing worth it for SpaceX? Let’s look at some numbers. NASA Spaceflight reported that leasing Ms. Tree could cost about $7,500 a day, or $2.7 million a year. However, SpaceX likely has a long-term contract with the ship’s owner, so the actual price may be lower. With these numbers, just one recovered fairing half (costing about $2 or $3 million) covers SpaceX’s lease costs for a full year. However, these costs don’t include development, wages, fees and so on.

But still, it’s reasonable to assume that even if the overall fairing recovery success rate was fairly low (say, 50%), it would be still be worthwile for SpaceX. Also, because it’s possible to reuse fairings that have soft landed in the water, landing in the net isn’t critically important (but would still be preferable compared to to splashing down in the ocean). To illustrate this: There were 14 fairing reuses between the introduction of the v2.5 fairing in April 2019 and the end of 2020, but only about quarter of these had been recovered by landing in a net.

List of fairing recovery attempts

Our detailed list of all fairing attempts can be found on a separate page.

Did you enjoy this article? Check out similarly detailed Compendiums about other SpaceX topics: Starship, Falcon Heavy, OctaGrabber and more…

Changelog:

- Dec 23, 2020 – Added new milestones from recent months (triple fairing reuse and first reuse on a non-Starlink mission)

- Sep 1, 2020 – Added a video from the successful fairing catch during the Starlink v1-10 mission

- Jul 26, 2020 – Added information and video about the first successful double catch during the ANASIS-II mission

- Mar 21, 2020 – Added information about a second set of reused fairings that flew on the Starlink v1-5 mission; added a link to our new list of fairing recovery attempts

- Dec 14, 2019 – Replaced a deleted video and added information about first ever fairing reuse on the Starlink v1-1 mission

- Nov 5, 2019 – Fairing from the Arabsat 6A mission will be reflown on Starlink v1-1, making it the first time fairing is reused

- Aug 11, 2019 – Added information about the second fairing-catching ship called Ms. Chief

- Aug 7, 2019 – Created a new secton called First successful recoveries and added a new video from the second successful recovery during the Amos-17 mission

- Jul 28, 2019 – Added Musk’s description of the fairing recovery process and some better photos of Amos-17 and Starlink v0.9 fairings

- Jul 6, 2019 – Added video of the STP-2 fairing catch

- Jun 26, 2019 – Added information about Mr. Steven’s new name and also about the first successful fairing recovery during the STP-2 mission

- May 25, 2019 – Added information about the Mr. Steven getting new arms and net + the recovery of the Starlink v0.9 fairings and the implications of them not having acoustic tiles

- Apr 12, 2019 – Added information about the recovery and future reuse of Arabsat 6A fairings + added a section about fairing upgrades

- Apr 9, 2019 – Article first published